Boosting Democracy through Civics

This will be on the test

By Bruce Watson

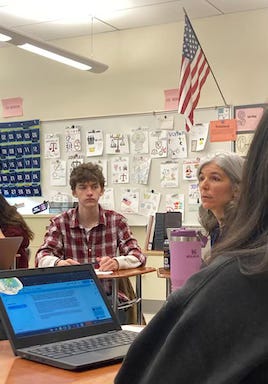

POST-ELECTION — EASTHAMPTON, MA — Slightly sleepy, sporting hoodies, jeans, and “wassup’s” for friends, nineteen juniors shuffle into Room 204 at Easthampton High. The time is 7:45 a.m but the classroom clock is hidden by a sign reading “Time to Learn.” And before students can slouch or even settle, the future of democracy stands at the whiteboard.

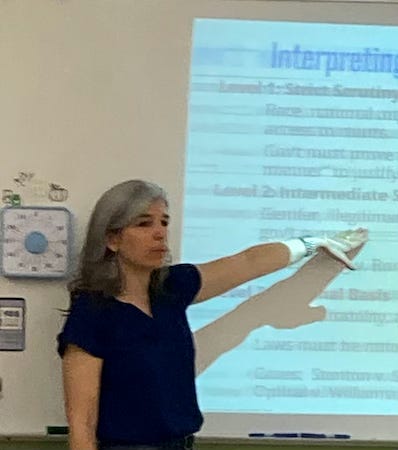

“I want to start with points of confusion,” Kelley Brown says. “What do you want me to clarify about the 14th amendment? And remember, this is the time to fail. You don’t need to know it all now.”

Brown is the teacher everyone should have for any topic. Yes, she has the creds — Massachusetts History Teacher of the Year (2010), National American History Teacher of the Year (2022), etc. But just watching “Ms. Brown” own her class “We, the People” is a lesson in itself.

“Okay, what is a fundamental right? Something so fundamental that. . .” With an American flag embroidered on her sweater, she strides among students, calling on a few, taking a phone from another, giving a handkerchief to one who sneezes.

“So fundamental that. . .”

“So fundamental,” a student finally says, “that it can’t be taken away.”

“Right.”

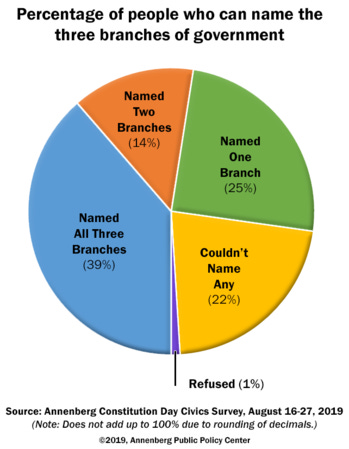

This will be on the test — of democracy. And We, the People are not exactly acing that test. Last February, when the U.S. Chamber of Commerce surveyed 2,000 adults, 70+ percent failed a basic civics quiz. Just half knew where bills are written into law. (Congress, duh.) A third could not name all three branches of government.

When the subject is Civics, the national report card is grim. Just nine states and D.C. require a full year of high school civics. Thirty-one states require just a semester, and ten states have no civics requirement. The upshot? While two-thirds of Americans remember studying high school civics, only 25 percent are “very confident” they could explain how our government works. The recent election, however, may change that.

With America now facing the gravest threat to democracy since the Civil War, more and more people seem ready to get back to civics. Some even see civics as a form of activism.

“Talking about voting and voting rights is another piece of grassroots work,” said Andy Bernstein of The Civics Center. The California-based group helps high schools organize voter registration drives, and gives teacher workshops on everyday civics.

“Our main purpose is to ask how we spread voter registration into every high school,” Bernstein said, “but we also ask how we motivate students to actually vote. That’s where civics comes in.”

Time was when “How a Bill Becomes a Law” was widely taught, almost a cliché. Now the phrase draws blanks. What happened?

“There wasn’t a concerted anti-civics movement,” said Richard Haass, former President of the Council on Foreign Affairs. Speaking on the podcast “How to Fix It,” Haass added, “It was a little bit like musical chairs. When the music stopped and we said we have to have a chair for STEM and for this and that, civics didn’t have a lot of backers. A lot of people wrongly concluded it was something of a luxury.”

Congress is considering bills promoting civics education, Haass noted, but because most educational funding and policy is local, few bills have any teeth. “Like a lot of things in this country,” Haass added, “the answer may not come from the top down. It may have to come from the bottom up.”

Several grassroots groups already focus on civics education. Along with The Civics Center, these include:

— The Center for Civic Education, sponsor of “We, the People,” the national civics competition that Kelley Brown’s students have come close to winning;

— ICivics, founded by former SCOTUS justice Sandra Day O’Connor, which engages some 9 million students nationwide with innovative games and activities for civics education;

— Generation Citizen, begun as a student project at Brown Univeristy and now working with 25,000 students nationwide.

— Citizen University, which teaches interested citizens to foster local interest in civics through “gatherings, rituals, and learning experiences for neighbors.”

Civics is also promoted by institutions from the National Archives to the League of Women Voters. But the activities and the curriculum of today’s civics are not necessarily those that once brought cries of “borrr-ing!!!”

Consider how Philadelphia’s Committee of Seventy teaches teachers to teach civics. The group, dating to the Progressive Era, took up civics as a cause several years ago. Since then, the Seventy have promoted new ways to teach the old subject. These include:

— “Can We Talk?” introduces habits that promote productive dialogue across difference, to counter polarization and division;

— “#VoteThatJawn,” using social media to bring 18-year-olds and other first-time voters into civic engagement';

— “Democracy for Kids,” helping K-8 studentspractice basic civic skills, like respectful listening, creative inquiry and thinking, and community problem-solving.

— “Draw the Lines” teaching kids about gerrymandering by letting them draw their own maps.

Civics, Richard Haass says, “is not a short term solution but an investment in our future.”

So what can the grassroots do? First, show up. Along with working for grassroots groups, we can go back to class. Kelley Brown, like many teachers, welcomes volunteers. Local lawyers, retired teachers, former students and their parents all show up regularly in Room 204 to tutor, ask questions, and show that they care about civics.

“Volunteers can draw a connection between community civic life and the classroom,” Brown said. “People with different experiences and points of view can show students how to apply political issues to their own lives and communities.”

As her class continues, Brown is all over the room. By 9:15, I am exhausted just watching her, but she concludes with reminders of next week’s oral exams.

And this test of democracy? Will America pass? Brown’s immersion in the Constitution gives her confidence. “We have enduring institutions that from time to time get tested,” she admits. “But I have confidence in American democracy. The founding generation thought hard about how to check human nature, and those checks and balances, plus a virtuous citizenry create the most ideal situation for our system to endure.”

Time for another class. Heading back to Room 204, Kelley Brown saves her strongest argument for last. Each election year, she says, she receives several photos from former students, proud “First Time Voters.”

“These kids make me hopeful. I really love them and I love what we do. I think we’ll figure it out. I put my hope in them.”

What a hopeful, inspiring piece! I'm so happy to know about the amazing Kelley Brown.

Instead of the communal handwringing that we hear coming from most news sources, teaching civics as described in this post is exactly, precisely what is lacking in our educational system and in the general discourse about many of our nation's ills.

I hope that others will read it and will share it widely!