By Steve Schear

“So Black voters are going to decide the election,” said Ron, a 40-year old in a Black neighborhood in Milwaukee’s northside.

When I saw Ron on his porch, I stopped, introduced myself and explained why I was there. “Why should I vote for Democrats rather than Republicans?” he shot back.

I was taken off guard. I couldn’t remember anyone asking me that at the beginning of a conversation. After a pause, I started in about Trump cutting taxes for the rich, and how Harris wanted to cut taxes for working people — with a child tax credit. And she will raise taxes on the rich and corporations. Then I told Ron what the Dems had done for old people like me — cutting costs of prescription drugs, and that Harris wants to do the same for everybody. Trump, I said, is only interested in himself and his rich buddies. Harris is trying to help working people.

Ron told me he liked to listen to both sides. And as we talked, I sensed him warming up to Harris. Then I told him about the low turnout in Milwaukee in 2022 and 2020, and that getting more people to vote here could make the difference.

“So Black voters are going to decide the election,” he said.

Of course, that’s not strictly true, but Ron was onto something. In 2020 and 2022, Democratic turn-out was also very low in Philadelphia, Detroit, and Charlotte. As Ron sensed, by getting tens of thousands more urban Democrats to vote this year, we can win in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and North Carolina. Win those states and we win the White House. And that’s very doable if we have enough friendly canvassers out in Black neighborhoods.

My Weekend in Milwaukee

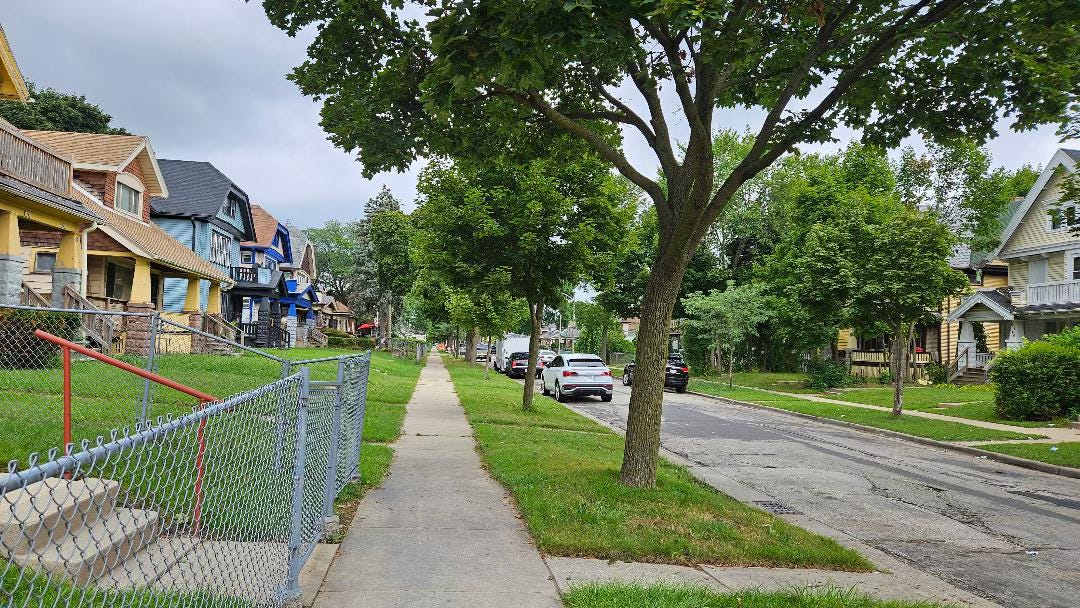

I was in Milwaukee last week-end, before the Democrats’ convention in Chicago. It was supposed to be a persuasion canvass, to convince people to vote for Harris, but persuasion was rarely needed. Almost everybody I met was already on board for Harris. They were supportive and friendly when they heard why I was at the door. And although I am a white guy, there was no hint of hostility or distrust.

So after two or three doors, I shifted from persuasion to activation. Every Black woman I talked to was behind Harris, often vehemently so. Older Black men were also universally behind Harris, although less passionately. The only Undecideds were younger Black men like Ron. And I met only one Trump supporter — Shane.

Spreading the Word — and Lawn Signs

When meeting anyone squarely behind Harris, I asked about volunteering. Deborah, a middle-aged Black woman, said she didn’t have time but would be willing to organize her block. When others said they could not volunteer, I suggested helping by telling friends and families to vote. Most agreed. Then I brought up Milwaukee’s low voter turnout, to emphasize the importance of reaching out to others. When voters were especially enthusiastic, I asked them to put up lawn signs. Eleven people agreed, enough to create a “Community for Harris” ambience in the eight blocks I canvassed.

Talking to People Not on the List

When I approached Cameron’s door, two young people sat on the steps. Cameron wasn’t home, they said. I told them who I was, and asked if they were of voting age. Both were 18 — were they registered? They were not, but were interested in politics. I couldn’t register them myself, because registration in Wisconsin requires uploading photo I.D.’s, but I gave them a leaflet for Harris and Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin with a voter assistance phone number. They promised they would register.

Talking With a Ranter

At another door, a thirty-something Black man was on the front porch. Seated nearby were two women, one middle-aged and one grey-haired. I told them why I was there, and the younger woman immediately voiced support for Harris. The man shouted.

“I’m for Trump!”

The woman yelled back — shouting that he was ignorant and should stop saying such stupid things. They yelled back and forth for a few minutes while I listened.

“Shane, I’m not talking to you any more,” the woman shouted. “I’m not talking to a Trump person like you!” She stormed off, leaving Shane to bolt off the porch and climb into his blue pick-up.

But Shane didn’t leave. After telling me the women were his mother and grandmother, he started yelling at me. Women should not abort babies, he shouted, and if women “open their legs and get pregnant they should keep the baby. And it should be the man who decides whether or not the woman has an abortion, because he put it in her.”

I listened for a few minutes. Then I said, “Yelling really doesn’t work for winning arguments.” Shane calmed down and we began to talk.

I asked if he believed that two cells, an egg and sperm, were a human being that shouldn’t be killed. Yes, he said, but he thought abortion was okay up to six weeks. Then, as I’ve often done, I said I respected people who believe that a human being exists at conception or that abortion should be illegal after six weeks. Or ten weeks, or fifteen, or viablity. But it shouldn’t be the government that decides, I said. It should be the woman and her family. Shane didn’t concede anything, but I could see he had lost confidence in his view. I also told him that Trump was only interested in himself, and didn’t care about people like Shane and his family.

After Shane drove off, I turned to his grandmother.

“You’ve got some work to do with Shane!” I said.

“Okay, thank you!” she answered, with a wave.

I told lots of people how important it was to talk to young Black men who were not supporting Harris, because they were more likely to listen to them than to me. Some said that such men wouldn’t listen. Try listening first, I advised. Listening a lot, and asking questions, before trying persuasion. Something like two-minute classes on deep canvassing . . .

The Birthday Party and Ava

That Saturday was the most fun I’ve ever had canvassing. When a front door sign read, “Use other door,” I walked around to the side and found ten men celebrating a 54th birthday, drinking and smoking weed. I told them who I was, and several asked for leaflets. One asked me about Project 2025.

“You know about that?” I said. He asked if I was surprised he knew about Project 2025, checking my white arrogance quotient. “Some people know,” I said with a shrug, “and some don’t.” He seemed fine with that. He told me he taught fourth grade, and insisted that I share their weed. I hung out for 20 minutes, talking more about weed and personal histories than about politics, with lots of laughter in between.

But my favorite conversation was with Ava, a skinny girl, about six years old, who I saw standing on the sidewalk. I leaned down and asked, “Did you know a Black woman is running for president?” She shook her head. “Yes,” I told her, “Kamala Harris is a Black woman who is going to be the next president.” Ava looked up and said softly, “I want to be president when I get older.”

“That’s great,” I said. “I’ll be able to say I knew you when you were only a girl.” I left Ava, energized to do more canvassing.

Your story reminded me of some of my happiest canvassing moments. The best most interesting and energizing conversations were always in black neighborhoods, and I as an older white woman always felt completely safe. It was only in a white upwardly mobile neighborhood in Florida where a white guy came screaming out of his house and yelled at me for canvassing for Hilary that I realized how fortunate I was that this rarely happened.

Thank you so much for doing this work, Steven! You make me want to go to Milwaukee!